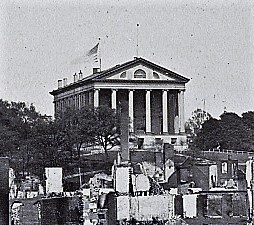

Federal Flag over Richmond, April 1865

Image courtesy of Library of Congress

After four long years of blood and war, Union Troops on the morning of April 3, 1865 entered the city of Richmond, Virginia, then capital of the Confederate States of America. Richmond had become the single-minded focus of the Union war effort, in a civil war between Americans of Northern and Southern persuasions that would claim an estimated six hundred thousand combatants. As southern soldiers, officials and sympathizers abandoned Richmond to advancing Union forces on that early morning in 1865, retreating Confederate soldiers set fire to grain and tobacco warehouses. The blaze spread quickly and left a significant part of the city in ruins. Through the chaos of evacuations, sporadic skirmishes and raging fire, one of the first of many Union troops to enter Richmond included a company of men with the Thirteenth New Hampshire Regiment. The memoirs of the regiment have been compiled and published in the “Thirteenth Regiment of the New Hampshire Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion” by S. Millet Thompson, an officer with the regiment. Thompson provides a vivid and detailed account of the events of April 3, 1865, at the fall of the Confederate capitol:

“… There was no flag on the roof of the capitol when I entered the grounds, but within a few minutes it suddenly appeared on the flagstaff on the roof, and immediately afterward I had a conversation with the man who raised it. He was a light colored boy named Richard G. Forrester, living on the corner of College and Marshall. When the State of Virginia passed the ordinance of secession, he was a page or errand boy employed in the capitol. The secessionists tore down the flag and threw it among some rubbish in the eaves at the top of the building. At the first convenient opportunity, he rolled the flag in a bundle, carried it to his home and placed it in his bed, where he slept on it nightly since that time. This morning, he said, as soon as he dared after the Confederates had left the city, he drew the old flag from its hiding place, ran to the capitol with it, mounted to the top and ran the flag up the flagstaff. This was the first flag hoisted in Richmond after its evacuation by the Confederates.”

Forrester Affidavit

-13th NH Regiment Book

Four years earlier, Virginia’s ordinance of secession was ratified on May 23, 1861. Shortly after, the newly constituted Confederate Congress would declare Richmond as the new center of the Confederate States of America. The announcement drew wild celebration on the capitol grounds that was thronged with thousands of rebel revelers. As the federal flag was struck down from atop the capitol building and thrown into the rubbish to be later burned, Richard Gill Forrester, amid the chaos of celebration, rolled the flag into a bundle and carried it to his home a short distance away on College Street. Once home, unknown to his own family, he placed the flag under his bedding, where he would sleep on it nightly for the entire four years of the war. The risk he took rescuing and preserving what was seen by nearly all Southerners at the time, as the symbol of Northern aggression and invasion, was significant.

The city scene on that early morning in April 1865 after four long years of war, was one of turmoil. As fires rage across the city, streets were crowded with people, black and white, slave and free, looting stores and warehouses that were wrecked and abandoned with the approach of Union troops. Some accounts reported that barrels of liquor had been emptied into the streets, the more reckless drinking the running spirits directly from the gutters. In all the fire, smoke and confusion, Richard dashed across onto the capitol grounds and made his way up the spiral staircase that led to the roof of the Confederate capitol. There and then, he replaced Old Glory in advance of arriving Union troops.

Who was this young man and what were his family and life experiences within Civil War era Richmond that would drive him towards such an act of Union patriotism or Southern treason depending upon the point of view of the day? Richard was born into one of Richmond’s prominent free families of color in 1845. His paternal grandfather, Gustavus A. Myers, a successful lawyer and President of the Richmond City Council was a part of Richmond’s earliest Jewish families and during the war years he served as special counsel to Great Britain for the Confederate States of America. Richard’s father, Richard Gustavus Forrester was an offspring of Gustavus Myers and Nelly Forrester, a free woman of color who lived her entire life with members of the Myers family. Richard Sr. was a prosperous dairy farmer and contractor and after the war, would become the first man of color to serve on the Richmond City Council and School Board during the turbulent days of southern Reconstruction.

Young Richard grew up in a multi-racial, cultural and religious family structure that had one important commonality, members could trace themselves back to the founding days before the American Revolution. Richard adored and would be greatly influenced by his great aunt, Catherine Hays who would entertain him with stories of being born in 1776, the year of our nation’s birth, and growing up amidst the upheaval of the American Revolution era in Boston and Newport, Rhode Island. Catherine Hays was also described as a highly opinionated woman with strong “Abolitionist” tendencies, that often times placed her in ideological conflict with some members of her Southern family. She often would take young Richard on walks through Capitol Square, the park-like grounds surrounding the Virginia State Capital and point out the federal flag flying high above. She would reminiscence about seeing the earliest version of the American flag as the fledgling United States fought Great Britain for national independence.

As a member of a Sephardic Jewish family who would escape Old World religious persecution to settle in Newport, Catherine Hays knew far too well the challenges of being part of a minority group and the desire for the young country’s acceptance regardless of their religious belief. Great Aunt Catherine’s ideals along with Richard’s strong family upbringing, would spark a belief in him that would inspire him to carry out that great deed years later as the country was at the very brink of civil war.

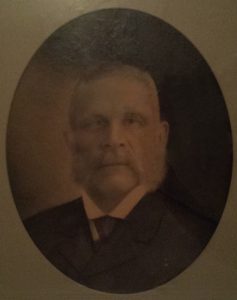

Richard Gill Forrester c. 1885

Image courtesy of Stokes Family

After the war, Forrester was appointed to a coveted federal position with the United States Post Office Department during Reconstruction era Richmond. He later moved north to New York City with his young family and took a position with the New York and New Haven Railroad, frequently summering in Newport, the historic home of his Jewish ancestors and where his beloved Aunt Catherine is buried. He lived a full and active life and was laid to rest at the historic Island Cemetery in Newport on Nov. 15, 1909, with military honors by the Lawton and Warren Post No. 5 of the Grand Army of the Republic. His front-page obituary in the New York Age, the leading African-American newspaper of the day, was quoted as saying, “There passed away a soldier who came into prominence by gaining the distinction of being the first man who hoisted the Union flag in Richmond after the Civil War.”

The veterans who buried him honored him as a soldier for his heroic deed. More importantly, why would a young man of color be moved to protect the federal flag that flew over the building that served as the capital of the Confederate States of America? During a time in our country when nearly all persons of African heritage, slave and free, North and South were seen as non-citizens, his actions would provide no future guarantee of civil liberties for himself and family. His daring efforts were well before the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution and a Civil Rights Act that wouldn’t be achieved for another one hundred years of reconstruction and reconciliation before becoming law in 1964.

Perhaps young Forrester acted because, although a Virginian, he believed the state was part of an America that, while not perfect, was and will always be a country of opportunity for all of its people — regardless of race, religion, ethnicity or nation of origin. As he had learned from his great aunt, the American Revolution would bring freedom of religion to all American people and the end of the Civil War could bring personal freedom to all American people of all races. And just maybe, after four years of blood and war, young Forrester and the country were looking for a symbol of a unified America: our American flag.

Historical sources and further reading:

1. “Thirteenth Regiment of New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865:A Diary Covering Three Years and a Day,” Thompson, S. Millet, Houghton, Mifflin, 1888

2. “Personal Memoirs: Phillip Henry Sheridan,” The Century Company, 1890

3. “The Stars & Stripes and Other American Flags,” Peleg D. Harrison, Little, Brown & Company, 1908

4. “A Flag & A Family,” Theresa Guzman Stokes, Virginia Cavalcade Magazine, Spring, 1998

5. “Richmond: The Story of a City,” Virginius Dabney, University of Virginia Press, 2002

6. “American City, Southern Place- A Cultural History of Antebellum Richmond,” Gregg D. Kimball, University of Georgia Press, 2000

7. “Virginia at War: 1861,” William C. Davis, University Press of Kentucky, 2005

8. “The Wars of Reconstruction,” Douglas R. Egerton, Bloomsbury Press, 2014

9. “Richmond Burning: The Last Days of the Confederate Capital,” Nelson Lankford, Penguin Group, 2003

10. “The American Journey: A History of the United States Combined Volume,” Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2006

11. Obituary of Richard Gill Forrester, New York Age Newspaper, November 25, 1909

12. When Freedom Came, Richmond Free Press, April 2015 by Elvatrice Belsches

- Saving Old Glory - March 31, 2023

- Keith Stokes receives Outstanding Achievement in Leadership Award - December 22, 2022

- Harriet Jacobs - December 22, 2022

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

March 30, 2017 at 2:21 pm

Keith,

Again thanks for meeting with Mike and me yesterday. Looking forward to collaborating with you on our Memorial Day activities.

This was an absolutely fascinating bit of history I was not aware of. Thank you.

Sincerely,

General Valente